[ad_1]

Study selection

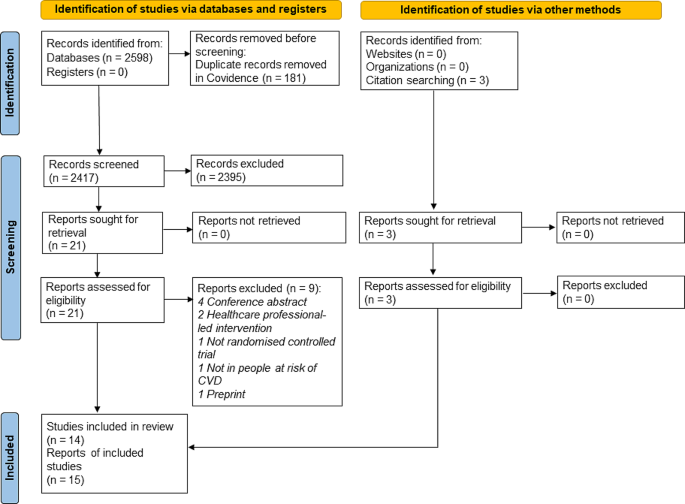

Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow chart illustrating the study selection process. The systematic database search yielded a total of 2598 records. After eliminating duplicates, 2417 titles, and abstracts were screened. Next, 21 full texts were sought for retrieval and then assessed based on the eligibility criteria. Most reports were excluded due to conference abstract (n = 4) and two were interventions delivered by healthcare professionals. A manual search of the included papers’ reference lists and citations was done and yielded three additional records. Subsequently, 15 articles representing 14 unique studies that matched the predefined criteria were finalised for this review. The details of included studies were summarised in Supplementary Table S3.

PRISMA 2020 flow chart showing the study selection process

Study characteristics

The general characteristics of the included studies are summarised and presented in Table 1. Of the 14 unique RCT studies, three were pilot RCTs. The sample size for pilot RCTs ranged from 31 to 114 individuals, while the RCTs ranged between 223 and 3539 individuals. With regards to the study origins, there were five studies conducted in America [22, 25, 31, 34–35], five in South Asia [26,27,28,29,30], followed by four studies in the Europe region, whereby three were in the United Kingdom [21, 32, 33] and one in Spain [23, 24]. Five studies targeted low-income populations [21–22, 25, 27, 34], and two studies focused on rural regions [28, 30]. The pilot study by O’Neill et al. (2022) focused on established community groups instead of individuals, including the peer support group and minimum support group [33]. Most of the studies (6/14) were conducted among participants at moderate to high risk of CVD as specified using a risk score [28, 32] or having at least two risk factors [26, 31, 34, 35]. Except for a study by Wijesuriya et al. [26], that included participants both under and above 18 years old, the mean age of participants ranged between 42 and 63.5 for all the included studies. The recruitment sites were scattered throughout various community locations [22–23, 25–26, 30,31,32,33, 35] as well as households [28–29]. Participants were also recruited using practice lists [21], voter lists [27], and administrative data [34]. Most studies (9/14) had study evaluation up to at least a year, while there was a study using end-point evaluation with median of three years of follow-up [26].

Study quality assessment

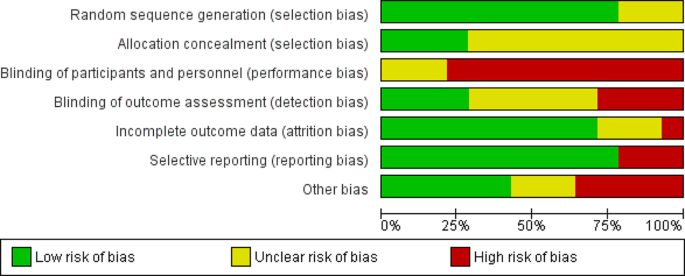

All the included trials were of acceptable quality as shown in Fig. 2. However, a high risk of performance bias was detected for most of the studies. This is due to the administration of lifestyle interventions that precluded blinding of participants and personnel. As for selection and detection biases, most studies did not address the allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessment, leaving the risk substantially unclear. The risk of attrition bias in the included studies was considered low due to the inclusion of intention-to-treat analysis in five studies [21,22,23, 31–32] and multiple imputation in three studies [25, 30, 34]. Besides, the reason for missing data was addressed as not related to outcome measures in one study [28]. While there was no serious issue pertaining to reporting bias, selective reporting was present in three studies. For instance, certain outcomes were stated in the trial registry or measured during data collection, but these were not reported in the study [26, 29, 33]. As for the risk of other bias, it was considered high in five studies due to a lack of sample size justification [21–22, 33–34] and study with an unequal number of subjects at baseline [27].

Risk of bias summary of included studies (n = 14)

Intervention characteristics

As we included lifestyle interventions facilitated by peers or community members, the intervention providers came in various designations, namely lay health trainers [21], community health workers and volunteers [22, 25, 27,28,29,30, 35], peer educators [23, 26], peer leaders [31–32], peer supporters [33], peer health coaches [34]. Collectively, we named these intervention providers as peer leaders thereafter. Most of the interventions (71%) lasted for a year [23, 25,26,27,28,29, 31,32,33,34]. Meanwhile, the shortest intervention duration was three months [21, 30] and the longest was the study using end-point evaluation with a median three years of follow-up [26]. In half of the included studies, the control groups received usual care lifestyle advice and/or written health information [21, 25,26,27, 29–30, 34]. Meanwhile, an educational program was provided to the control group participants in 5/14 of the studies [22, 24, 31,32,33]. All the included studies involved peer leader training prior to intervention and the various roles of peer leaders are described below.

Peer leader training

The duration of peer leader training varied from three hours to four weeks. The components of the training are presented in Table 2. The skills to deliver interventional modules and health information were the most important components in all studies, followed by communication skills (8/14) and research-specific skills (8/14). Research-specific skills included survey methods, measuring, recording, reporting, and following up [22, 25, 27,28,29,30, 34–35]. Five studies highlighted the emphasis on motivation skills, wherein peer leaders were trained in motivational techniques [34–35] and equipped to motivate participants for long-term behaviour change through the establishment of short-term goals [21, 24, 30]. Besides that, peer leaders were supported with motivational sessions by psychologists [23] and monthly training refresher sessions [26]. Leadership skills were trained in four studies [23, 31,32,33], group facilitation skills were emphasised in three studies [30, 32–33], while subject engagement skills were provided in two studies [21, 35].

Peer leader roles

The roles of peer leaders of each intervention are depicted in Table 3. Most peer leaders had at least two roles when delivering the interventions. There were seven studies conducted individual meetings [21, 25,26,27,28,29, 34] while group meetings were conducted in six studies [23, 30,31,32,33, 35]. Intervention by Koniak-Griffin et al. was the only study that involved group education followed by individual teaching and coaching [22].

a 8-weekly group education was provided by peer leaders prior to individual teaching and coaching.

b Individual coaching.

c Group education.

The individual meetings were done via home visits plus phone calls or text messaging, ranging from a weekly to quarterly frequency. Among the seven studies that included individual sessions, all the peer leaders provided advice on healthy diet and lifestyle behaviours [21, 25,26,27,28,29] while health coaching modules were completed in one study [34]. Five studies included progress monitoring by measuring blood pressure [25, 27,28,29, 34] and readiness to change was assessed in another two studies [21, 26].

In studies involving group sessions (n = 6), all meetings were held monthly, with each session lasting between one to two hours [23, 31,32,33, 35], except for the study by Gamage et al. [30], which conducted education and monitoring fortnightly. During the meetings, the peer leaders were responsible for delivering education and facilitating discussion, reflection and experience sharing on healthy dietary and lifestyle behaviours to reduce CVD risk among group members. Challenges and improvements for behavioural changes were also discussed. Two interventions had the core educational content to promote adoption and adherence to the Mediterranean diet [32–33]; thus, practical food demonstrations were conducted during the meeting sessions. Peer leaders also organised other dynamic activities, including menu design, sporting activities and relaxation techniques [23]. Four studies involved progress monitoring and feedback by peer leaders [23, 30, 32, 35], while goal setting was carried out at each group meeting in four studies [23, 32–33, 35].

Other support/ resources

In addition to meetings with peer leaders, several other forms of support and resources were provided to the intervention group participants. For instance, participants received a health handbook containing information on CVD prevention, and it was used to record lifestyle behaviour, health parameters and immediate goals [23]. In studies promoting the Mediterranean diet, both control and intervention groups received written educational materials. However, only participants in peer support groups were given a personal workbook to facilitate dietary goal setting and self-monitoring of personal dietary goals [32–33]. To promote preventive therapies, participating households were provided short goal-directed slogans printed on common household objects [28]. Additionally, to facilitate blood pressure monitoring, participants in the intervention were provided with blood pressure monitors in three studies [25, 34, 35].

Outcomes

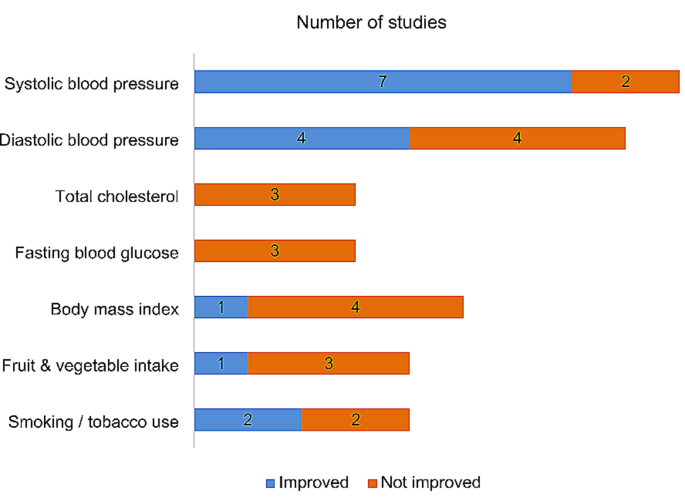

All study outcomes reported in the included studies are presented in Supplementary Table S4. Due to the variability of the study aims and intervention designs, the extracted outcome measures are broadly classified into clinical outcomes, dietary and lifestyle behaviour outcomes, and other outcomes for comparisons. Figure 3 summarises the CVD-related outcome measures of the included studies. One pilot study without hypothesis testing [33] was excluded from the outcome comparison.

CVD-related outcomes of the included studies (n = 13)

Clinical outcomes

Systolic blood pressure was the most common clinical outcome reported in 9/14 studies, out of which seven showed improvements post-intervention [25, 27,28,29,30, 32, 35]. Nonetheless, only five interventions showed significant differences between groups at follow-up [25, 27, 29–30, 35]. While four studies showed significant changes in diastolic blood pressure over time, the changes were similar between intervention groups in study by McEvoy et al. [32]. In the other studies, significant differences were observed between control and intervention groups [25, 30, 35]. Total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides were not showing improvements in all four studies that assessed these outcomes [21–22, 32, 34].

Fasting blood glucose was assessed in three studies, with no significant changes observed post-intervention [22, 29, 32]. Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels were assessed in only two studies [32, 35], and improvements were observed across intervention groups (minimal support, peer support and dietitian support groups) in study by McEvoy et al. [32]. Out of five studies, only one showed improvement in body mass index (BMI) [32]. Waist circumference was significantly decreased in one intervention [22], and another intervention notably reduced the cardio-metabolic endpoints, including new onset hypertension and dysglycemia [26].

Dietary outcomes

Six studies assessed the dietary outcomes relating to cardiovascular health using various parameters. The fruit and vegetable intake were improved from baseline in only one of the four studies [21, 27, 30, 35] that assessed this outcome, but the changes were not significantly different from the control group [21]. The intervention by Koniak-Griffin and colleagues significantly improved heart-healthy dietary habits among the interventional subjects [22]. The Mediterranean diet scores, as in the study by McEvoy et al. were improved across the intervention groups [32]. Intervention by Gamage et al. demonstrated greater reduction in added salt intake and alcohol consumption than in the usual care group [30]. Meanwhile, study by Shah et al. significantly showed reduction in sugar sweetened beverage intake in both intervention and control groups [35].

Lifestyle behavioural outcomes

The study by Shah et al. [35] was the only intervention that significantly increased self-reported physical activity levels out of five studies that assessed this outcome. Nonetheless, the step counts measured in the study by Koniak-Griffin et al. were significantly improved at the 9-month follow-up, and the changes were more significant than in the control group [22]. Two out of four studies reported improvements in smoking and non-smoked tobacco use habits [28, 30] but only intervention by Gamage et al. demonstrated significant change between intervention and control groups [30].

Other outcomes

The Fuster-BEWAT score (FBS), which is a health metric assessing the CVD modifiable risk factors (blood pressure, exercise, weight, alimentation, tobacco) was measured in two interventions [23, 24]. Gómez-Pardo et al. reported that, at 1-year follow-up, the intervention group showed significantly higher overall FBS levels, and a greater increase compared to the control group [23]. However, the 2-year follow-up showed no notable differences between the groups in terms of the average FBS or changes in FBS post-intervention [24]. Another 1-year intervention study also did not show improvements in FBS [31]. Three studies assessed health-related quality of life [21, 31, 34], but only study by Nelson et al. [34] showed significant improvement in mental component summary in intervention group. The INTERHEART risk score declined significantly across the studied households [28]. Two out of three interventions improved adherence to antihypertensive drugs more significantly than control group [28, 35]. One study reported significant improvements in heart disease knowledge post-intervention [22].

[ad_2]

Source link