[ad_1]

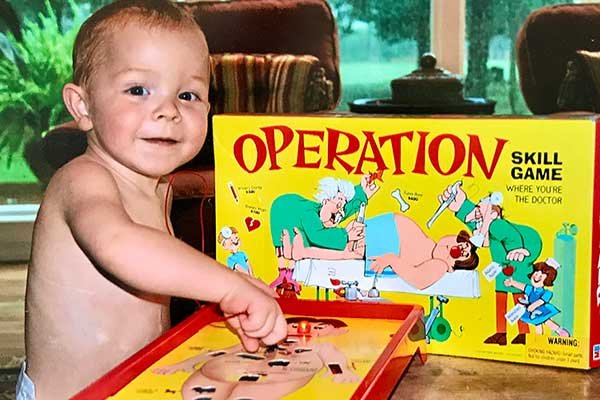

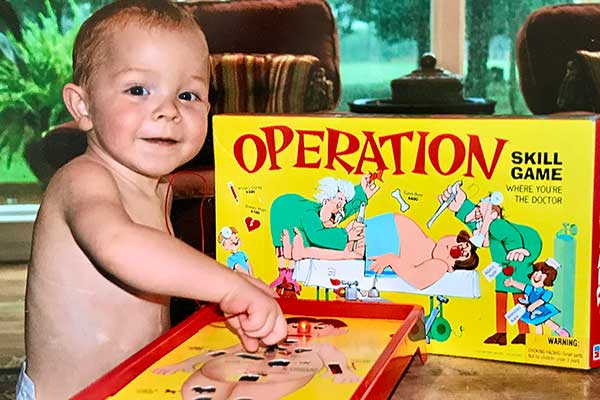

Nicholas DeHart was eight years old when he decided to join the school band. He chose the wind instrument clarinet. Normally this wouldn’t be a big deal, but for his family and doctors it meant a victory. That’s because Nicholas was born without a pulmonary artery (the blood vessel that carries blood from the heart to the lungs for oxygen).

A lifetime of care from the Pulmonary Artery Reconstruction Program at Lucille Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford University helped Nicholas achieve more than anyone could have imagined. Mr. Nicholas, now 13 years old, recently ran his mile fastest in his class and was voted first place on his flag football team at his home state of South Carolina school.

Diagnosis of Tetralogy of Fallot

In May 2003, Nicholas appeared healthy and strong as a newborn. As a fetus, Nicholas developed several major aortopulmonary collateral arteries to compensate for his missing pulmonary artery. These small, fragile blood vessels carried blood from his heart to his lungs, but they couldn’t sustain him for long.

Doctors soon diagnosed him with a complex congenital (meaning present at birth) heart condition called tetralogy of Fallot, which causes lung atresia. Tetralogy of Fallot occurs in approximately 1 in 1,000 infants and is associated with four heart defects. If the symptoms also include pulmonary atresia, it means the patient has the additional complication of a defective or missing pulmonary valve, as in Nicholas’ case. Nicholas, who had Tetralogy of Fallot, the most complex form, was missing not only his pulmonary valve but also his pulmonary artery.

Nicholas’ mother, Stephanie DeHart, a nurse anesthetist in South Carolina, immediately set to work researching medical teams across the country that were best suited to treat Nicholas’ baby. That’s when she found Dr. Frank Hanley, director of the Betty Eileen Moore Pediatric Heart Center and chief of pediatric cardiac surgery at Packard Children’s Hospital.

“Other doctors I talked to had done one or two of these repairs,” Stephanie said. “Dr. Hanley was the only person to have done more than 100 jobs, more than anyone else in the field.”

Dr. Hanley, who is also a professor of cardiothoracic surgery at Stanford University School of Medicine, has developed a one-stage surgical repair for tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary atresia. Before Hanley’s advances, surgeons repaired this complex condition in multiple surgeries over months or years. But Hanley’s approach of carefully opening each small collateral artery longitudinally and stitching them together to create a new pulmonary artery (a procedure called monofocalization) made it possible for the treatment to become his one-time revolutionary. was condensed into a 12-hour surgery.

“The defect manifests differently in each patient,” explains Hanley. The majority of patients (approximately 70 percent) are candidates for one-stage repair. “Nicholas was among the 10 per cent of patients whose condition was so complex that it required three surgeries to completely repair his heart.”

Single focus surgery

Dr. Hanley and his team performed Nicholas’ first surgery in November 2003, an 11-hour monofocal surgery on his left lung. Monofocal surgery on Nicholas’ right lung, which took him 12 hours, took place six weeks later. And in April 2004, Nicholas underwent his third surgery in his 6 months. In this final surgery, Dr. Hanley repaired his four associated heart defects, which make up Tetralogy of Fallot, and connected his heart to the reconstructed main pulmonary artery.

Because Hanley and his team follow a strict protocol, these surgical repairs, whether one stage or more, have a 98% success rate. “We use very strict criteria to perform definitive heart repairs, even in patients like Nicholas who require three surgeries to achieve their goal.” Dr. Hanley says. “We only perform this procedure when we are almost guaranteed that the patient’s blood pressure is adequate. In this way, even in the complex category, Nicholas’ outcome is similar to that of most other patients. You can expect it to be.”

“Here, the surgeries performed early in life are unique, and the results are unparalleled,” said Dr. Mick, medical director of the Lung Reconstruction Program at Packard Children’s Hospital and Stanford Graduate School of Cardiothoracic Surgery. says Dr. Doff McElhinney, a professor of pediatrics. medicine.

“But this is not a curative surgery or series of surgeries. Patients will still require ongoing evaluation and care. Part of that care includes the pulmonary valve used to repair it early in life. Other procedures may be included, such as replacing the conduit. In some cases, subsequent procedures may be surgical or endoscopic, such as the Melody valve, the most recent procedure Nicholas underwent here. It may also be done using a catheter pulmonary valve.”

continuing care

Dr. McElhinney added that even a heart that is properly repaired and has excellent function can still look abnormal, anatomically speaking. Therefore, children like Nicholas require specially trained eyes for follow-up care. “We have knowledge and experience with the whole lesion, which helps us determine what kinds of abnormalities are important and what are not,” says McElhinney.

Because of that unique knowledge, the DeHart family continued to return to Packard Children’s Hospital for Nicholas’ major care needs over the years, including a pulmonary artery replacement in 2007 and several catheterizations. Most recently, in August 2016, Dr. McElhinney and his team used a catheter to implant Nicholas’ Melody valve. The Nicholas Melody valve is a valve that is inserted without opening the heart and can last longer than the original surgically implanted valve, potentially for many more years.

Over the past year, Packard Children’s Hospital has ramped up its pulmonary artery reconstruction program, inspired by patients like Nicholas. Jennifer Sheck, a dedicated nurse practitioner, serves as the program coordinator and coordinates referrals and care for patients who come from all over the world to receive the unique care offered here.

“We are working to more effectively and comprehensively understand and address the lifelong course of this disease for these patients,” Dr. McElhinney says. “We are now taking a more active role in helping families and their doctors before they come here for their first surgery. And we are building deeper and broader relationships with each patient and family. We are helping to foster and enhance the patient experience before they arrive, while they are here, and after they return home (often to other states or hospitals).”

Last year, Nicholas traded in his clarinet for a trumpet and took acting and voice lessons. “Nicholas is a fun boy. He’s funny, kind, active, and adventurous,” says Dr. McElhinney. “He’s a great example of how kids living with heart disease can be everything. As a cardiologist or heart surgeon, that’s incredibly rewarding.”

[ad_2]

Source link