[ad_1]

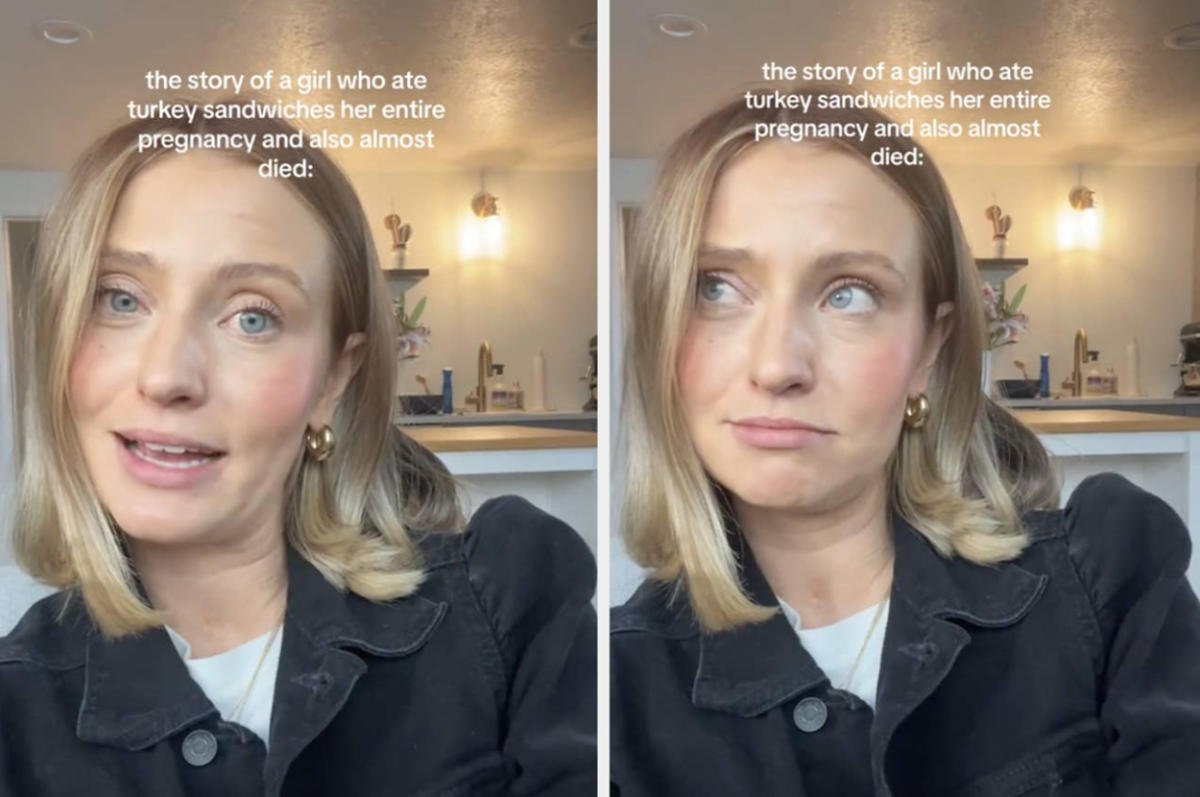

Jen O’Neill was only 36 years old and was not considered a priority patient in the emergency department because of a suspected heart attack.

O’Neill, who gave birth 11 months ago, had no traditional warning signs of a heart attack, such as a family history, high blood pressure, diabetes or high cholesterol levels, but her troponin levels confirmed the problem in her mind. It was there.

When she finally underwent a scan, she was diagnosed with spontaneous coronary artery dissection (Scad), which occurs when there is a tear in the artery that supplies blood to the heart. More than 9 out of 10 people are women, and many have just given birth.

However, there was no research into the optimal course of medication for this condition, so O’Neill was given the same course of blood thinners and beta-blockers used for traditional heart attack patients.

The blood thinners made my periods very heavy and I felt extremely tired. They were also intended to prevent further heart attacks. However, O’Neill experienced two additional hardships.

“We don’t have a gold standard treatment for SCUD. My understanding is that much of the research is based on men, because men are the traditional heart attack patients,” Professor O’Neill said. Told.

Now, a new national research center will be dedicated to improving knowledge gaps about how sex and gender influence the risk, detection and treatment of many health conditions, and translating that research into policy and practice. I will do it.

The Center for Sex and Gender Equality in Health and Medicine opens at the University of New South Wales on Wednesday, an initiative of the George Institute for Global Health, the Australian Human Rights Institute of New South Wales and Deakin University, with support from Victoria State University. Inaugurated. Department of Health and Australian Association of Medical Research Institutions.

Professor Robin Norton, founding director of the George Institute, said: ‘Our knowledge of health is overwhelmingly based on research done using male cells, male animals and male humans as standard in the laboratory. “This has to change,” he said. .

Ms Norton said Australia was “really far behind countries such as Canada, the US, Japan, South Korea and many European countries that have established centers focused on trying to understand the role of sex and gender in health equity. She said she and her colleagues are aware that the

The evidence base supporting health care has been strengthened by a report released earlier this month from the National Women’s Health Advisory Committee, established in late 2022 to address misogyny in health care and chaired by the Under-Secretary of Health. It was one of five areas identified as explaining the Health, Ged Kearney.

After newsletter promotion

Through research and advocacy, the new center will address the challenges of poor health outcomes, evidence gaps, and inefficient health spending for women, intersex people, transgender and gender diverse people, and, in some cases, men. Addressing gender bias in health and medicine.

For example, data on osteoporosis, which is considered primarily a disease of older women, shows that men are rarely treated for the disease and have higher mortality rates from complications of the disease than women. Masu.

“Frankly, I’m looking forward to this center as an opportunity to really work towards improving health outcomes and health equity for all Australians,” Mr Norton said.

The center has two hubs, one based at UNSW and the other at Deakin. Researchers from both universities will work on research that addresses health inequities, but the center will also serve as a resource for outside organizations and individuals across the country.

Norton said the center will also focus on translating research findings into policy and practice through collaboration with governments, health care providers and the business community.

[ad_2]

Source link