[ad_1]

April 7, 2024 — Strategies like earning points and small amounts of money helped people at high risk of heart disease and stroke increase their daily walking by about 10% and maintain that increase for a year. , the research results were published in an American academic journal. Annual Scientific Session of the Society of Cardiology. The study met its primary endpoint, demonstrating a statistically significant increase in participants’ daily step count from the start of the study to 12 months.

Dr. Alex Fanaroff

“This is one of the largest and longest-running randomized trials of a home-based intervention to promote physical activity,” said Alexander Fanarov, MD, assistant professor at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and lead author of the study. Ta. . “Our findings show that interventions based on behavioral economics techniques can achieve and maintain increased levels of physical activity in populations with risk factors for cardiovascular disease, reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease. It could be another mitigation tool.”

Behavioral economics is a field that uses concepts from economics and psychology to better understand and influence how people make decisions. Insights from behavioral economics can be applied to many other fields, including medicine and public health, Fanaroff said.

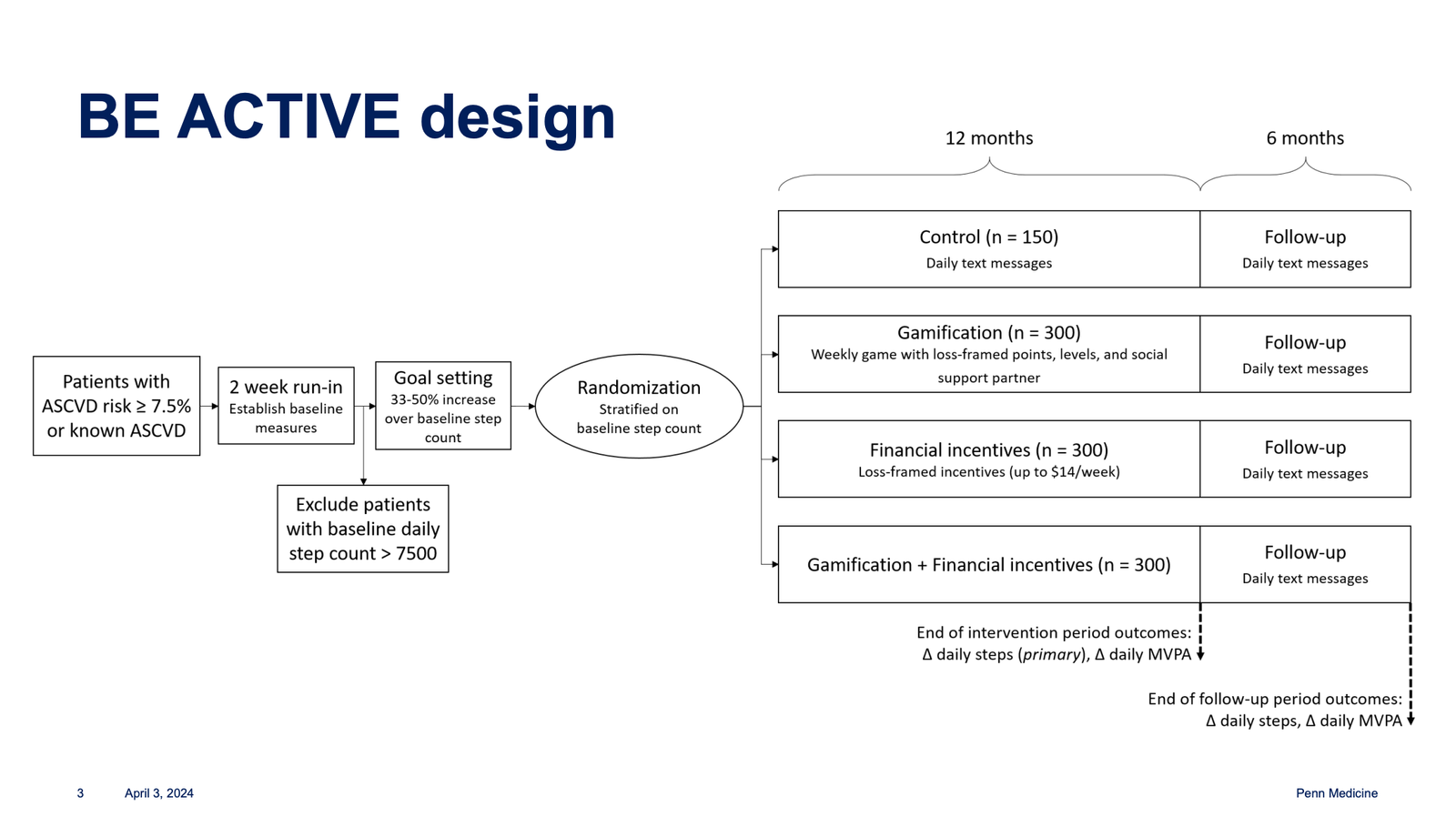

The BE ACTIVE study tested whether certain behavioral economics techniques could help people improve their daily walking levels. One technique known as gamification is the use of gameplay elements such as competition and point-earning. The other uses financial incentives, where people win or lose small amounts of money based on their actions.

“We know that physical activity is important for cardiovascular health,” Fanaroff said. “Many studies have shown that people who engage in more physical activity are healthier and have fewer heart attacks and strokes than those who engage in less physical activity. This is equally true for people who have had heart failure, have heart failure, or are at risk for cardiovascular disease.”

According to Fanaroff, only about 1 in 5 Americans regularly engage in 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per week (the amount recommended by many public health organizations), and that number increases with age. It is said that it will further decrease as time goes by. Although the widely known advice to take 10,000 steps a day is not based on scientific evidence, research has shown that increasing the number of steps you take by up to 7,500 steps per day can reduce your risk of dying from heart disease. He said there are. In fact, a study published in JACC: Heart Failure found that an increase in daily steps was associated with improved health over a 12-week period.

The BE ACTIVE study enrolled 1,062 people with a median age of 67 years, of whom 60% were women and 25% were non-white. One-third had household incomes of less than $50,000 per year. All participants either had cardiovascular disease or were at high risk for it. All participants received a wrist-worn fitness tracker that automatically uploaded their daily step counts to her secure website.

At the start of the study, participants averaged about 5,000 steps per day. Each participant was asked to select whether his goal was to increase his daily step count by 33%, 40%, 50%, or at least 1,500 steps above his level at the start of the study. Fanarov said previous research has shown that when people choose their own goals, they’re more likely to achieve them.

Participants were then randomly assigned to one of four groups. People assigned to the control group received a daily text message telling them how many steps they had taken the previous day. Participants assigned to the gamification group were awarded 70 points each week. Every day I met my step goal and maintained my points. I failed to reach my goal each day and lost 10 points. If at the end of the week she has earned 40 points or more, she has moved up a level. If you got less than 40 points, you moved down.

Participants assigned to the financial incentive group received $14 in their virtual account each week. Each day they met their step goal, but their balance remained the same. Every day he didn’t reach his goal, his balance decreased by $2. The fourth group received both gamification and financial incentive interventions. All participants in the three intervention groups received daily text messages informing them whether they had achieved their goals the previous day and encouraging them to keep trying.

The intervention continued for 12 months, after which all participants were followed up for an additional 6 months. During the follow-up period, participants no longer received the intervention but continued to receive daily text messages informing them of their step counts from the previous day. The study’s primary endpoint was change in daily step count from the start of the study to 12 months. Secondary endpoints included changes in daily steps and average weekly minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity from the start of the study to 18 months.

A total of 954 participants (89.8%) completed the entire 18-month study. After 12 months, compared to the control group, participants in the gamification group’s average daily steps increased by 538 steps, and those in the monetary incentive group increased by 491 steps. For participants who received both interventions, the average number of steps per day increased by 868 steps compared to the control group.

At 18-month follow-up, the group receiving both interventions was the only intervention group to demonstrate statistically significantly greater daily step counts compared to the control group. Nevertheless, across all three intervention groups, participants’ average daily steps increased by more than 1,500 at 18 months and their average weekly hours of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity increased compared to their step counts at the start of the study. increased by more than 40 minutes.

“While the gamification and financial incentive interventions were equally effective, the combined intervention was significantly more effective than either intervention alone,” Fanaroff said.

To date, no completely home-based intervention to promote physical activity has lasted longer than 24 weeks, and no total follow-up period has exceeded 36 weeks, he said. Participant engagement in the study remained high throughout the study period, he said. “During the 18-month follow-up period, step counts were uploaded on more than 80% of the participants’ days,” he said.

“In all three intervention groups, we observed an increase in daily step count from about 5,000 steps at baseline to about 10% more than the control group,” he said. “This trial did not collect data on participants’ health status. However, based on data from observational studies, an increase of this size was associated with a 6% lower risk of death from any cause and a lower risk of heart attack or stroke. “We estimate a 10% reduction in the risk of death due to the changes achieved in this trial, highlighting the clinical relevance.”

Fanaroff said a limitation of the study is that participants chose to enroll voluntarily and may not be representative of everyone eligible to enroll. Second, the researchers assessed physical activity using steps and active minutes, but did not assess whether other measures of participants’ health or functional status changed.

This research was funded by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health.

The study was simultaneously published online in the journal Circulation at the time of publication.

For more information, please visit www.acc.org.

Click here for detailed coverage of the ACC24 conference.

[ad_2]

Source link