[ad_1]

For 75 years, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) has studied a wide variety of diseases and conditions. and Can be crossed. Under Director Gary H. Gibbons, MD, NHLBI is participating in a number of initiatives aimed at tackling heart disease, combating the lingering effects of COVID-19, and reducing health disparities. Dr. Gibbons spoke with NIH MedlinePlus Magazine about some of these efforts and his personal interest in cardiology.

What made you decide to pursue a career in medicine? What was your path to becoming a cardiologist?

I was always a very curious child. I wanted to know how and why things worked. My parents were school teachers and they gave their children books that explained scientific concepts like the solar system, why the sky is blue, and how the body works. I grew up in Philadelphia and was blessed to have a free Franklin Institute for my kids. I was also able to take a bus or subway by myself and explore the science museum. I think it was a curiosity about how and why things work and that the body is an amazing system. I wanted to know more.

I wanted to understand why abnormalities occur in the body and how this relates to patients and people who suffer. Growing up in downtown Philadelphia, you encounter people with a variety of illnesses, especially those that are more common in the black community. That was the reason I became a cardiologist.

Cardiology is a field of medicine that deals with patients who have died and been resuscitated, or who are on the verge of death. And as a cardiologist, you can use your knowledge to get someone literally unable to breathe back to normal life within days or even hours. I have always wanted to become a doctor who can alleviate that suffering. That’s what I do today, just on a different scale.

How did you become NHLBI Director and why were you interested in the role?

It is perhaps the story of a winding journey. My goal in medical school was to become a family physician in a community like the one where I grew up. But that trajectory changed when I asked one of my professors why African Americans are more likely to have high blood pressure, stroke, and heart disease. as a result? As any good professor would do, he encouraged me to join his lab and pursue that question. The rest is history.

I spent my first summer in two years. I was once again bitten by the science bug and its curiosity. It broadened my horizons from just being a clinician to being a cardiologist and a scientist. I don’t just alleviate the suffering of patients. It also allowed me to try to understand the underlying causes of suffering and illness. It was very important in setting me on a research path, becoming an NIH-funded scholar, and later serving on advisory committees and research departments.

Since then, I have become more aware of the impact that NIH has beyond a single patient. It’s about improving the science of understanding heart, lung, blood, and sleep disorders at scale to improve the health of every community in our country. It’s a higher level of achieving the same goals that I wanted to achieve on a personal level.

How does NHLBI balance all the areas for which it is named: heart, lungs and blood conditions?

It’s also home to the National Center for Sleep Disorders Research, so add in sleep and circadian biology (the study of the body’s 24-hour cycle). You need to be aware of how those conditions differ. However, there are often scientific connections between the NHLBI’s separate divisions.

For example, our work on sickle cell disease leverages gene therapy and gene editing. This technology exists to capture the genetic code and manipulate it to improve human health and prevent disease. This may also apply to lung and heart diseases.

We often rely on statins and other drugs to lower our cholesterol. There may even be a way to engineer genes to lower an individual’s cholesterol for life. Lowering your cholesterol can help prevent heart attacks, strokes, and other illnesses. However, in the future, these other gene therapies may be used as alternative ways to reduce the risk of heart disease.

Those are the research topics.

Heart disease has been the leading cause of death in the United States for many years. Has our understanding of heart disease changed over time? Is there anything we can do to prevent heart disease?

It is important to recognize that great progress has been made. NHLBI was first established in 1948 as the National Heart Institute. At the time, heart disease surpassed infectious diseases as the number one killer in the United States. I couldn’t understand why middle-aged people were dying one after another.

One of the first things we did was establish the community-based Framingham Heart Study. This sets the stage for methods to study population and epidemiology. This helped identify risk factors that make you more likely to have a heart attack. High cholesterol, high blood pressure, and diabetes have all been shown to be risk factors for heart disease. We also realized that things like smoking can affect your risk.

This started a lot of research. As a result, heart disease has decreased by about 70% over the past 50 years. This is a testament to how NIH and NHLBI can advance the health of the nation through research and discovery.

Despite these advances, heart disease remains the leading cause of death. One thing that’s slowing progress is that translating the science into better health care for all communities, especially people of color, Native Americans, African Americans, rural people, or people of low socio-economic status. This does not mean that they are benefiting from it. They may live in environments that make it difficult to live a healthy lifestyle. They may not have a safe place to walk, or they may live in a food desert. Addressing health disparities in cardiovascular disease is an ongoing part of NHLBI’s strategic vision.

To that end, we created more heart research like Framingham in our most vulnerable communities. We also work to establish heart disease interventions in the community. One example is the NIH Community Engagement Alliance Against COVID-19 Disparities program, which draws lessons from the pandemic and supports community resiliency.

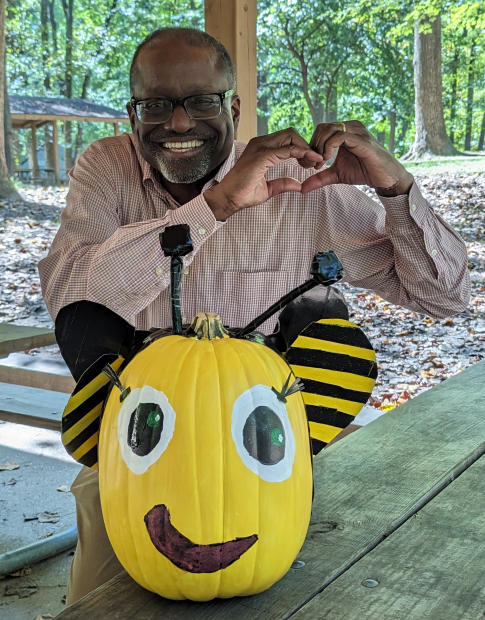

When Dr. Gibbons is not working, he likes to enjoy nature.

Another initiative inspired by the pandemic is the NIH Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery (RECOVER) clinical trial for long-term novel coronaviruses. How is NHLBI contributing to this project?

This is one of the post-viral syndromes seen in the medical field. SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes coronavirus disease) is a new and potentially contagious virus. [patients to develop] Long new coronavirus. [They can] They suffer from over 200 symptoms from each organ system of the body. Considering the vascular effects of COVID-19, it is logical for NHLBI to join her RECOVER. Blood clotting is part of the effect this virus has on the body.

We are making progress with the RECOVER consortium, which is comprised of research institutions across the NIH. Nearly 90 publications, both in and out of the pipeline, are already providing new insights into the duration of COVID-19 and its causes. There are also clinical trial platforms investigating specific symptoms such as dizziness and brain fog. We prioritized the symptoms that patients said were most meaningful in relieving their suffering.

One of RECOVER’s principles was to put the patient at the center of everything we do. We listen to them and their caregivers and reassure them that this is a new post-viral disease and that this is real and not in their heads. Patients have been involved in this initiative since its inception. We want to make sure that patients are developing protocols with researchers.

Extreme weather events are impacting air quality in unprecedented ways. What can people do to protect their respiratory health?

It is clear and undeniable that the climate is changing and that it is having an impact on health. The public is becoming more aware of these issues. It reminds us that we are all her one planet and that it is the key to increasing resilience and adaptation from climate impacts on our health.

It’s not just air quality. Heat stress also poses a threat to the cardiovascular system. Climate change also affects water and flooding. This also affects infections like the Zika virus, which affects the blood system and blood supply.

We need to respond to communities in ways that are tailored to local needs so that people can take steps to protect themselves if possible. For example, heat stress in urban areas can cause incredible temperature differences on asphalt roads and rooftops. This is especially harmful to the elderly. Simple interventions like cooling centers and encouraging communities to protect older adults can help people protect themselves. Children and pregnant women are also more vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Exposure to air pollution can have lifelong effects, including the development of asthma.

What advice would you give to someone who wants to become a cardiologist?

Being driven by feelings of compassion really helps. That, along with the desire to alleviate the suffering of others, is why many of us are drawn to becoming doctors in the first place. Generosity and selflessness motivate us as physicians, but we need to have that curiosity as scientists as well. Part of what science does is chip away at our ignorance. For someone like me who has been in the medical field for decades, there are many things I did as an intern that I no longer do. Scientific advances are critical to improving long-term patient care.

What do you like to do in your time outside of work?

It is important to maintain a mental balance in your life with family and friends. I love music, I love jazz and gospel. And I would like to be part of a church that would allow me to sing in the choir. Sometimes I go to the park and spend some quiet time with nature, whether it’s the ocean or the leaves of a tree. I feel it.

It is an important part of maintaining a healthy life and thriving overall as a person, including your mental health. Have compassion, have opportunities to help others, and live a balanced and meaningful life. We’re learning that it actually helps you live longer.

[ad_2]

Source link